The use of adequate, well-balanced nutrients for cattle can maximise profits or minimise losses in a feeding program. An animal’s diet must contain the essential nutrients in appropriate amounts and ratios. This fact sheet outlines the nutrients for cattle that are basic to good cattle nutrition, and how well balanced feeds succeed in supplying these nutrients. However, to better understand how feeds are used, it is important to understand the digestion process in animals.

The use of adequate, well-balanced nutrients for cattle can maximise profits or minimise losses in a feeding program. An animal’s diet must contain the essential nutrients in appropriate amounts and ratios. This fact sheet outlines the nutrients for cattle that are basic to good cattle nutrition, and how well balanced feeds succeed in supplying these nutrients. However, to better understand how feeds are used, it is important to understand the digestion process in animals.

Digestive systems – In the monogastric or single stomached system, e.g. the pig and man, the digestive tract is essentially a muscular tube extending from the mouth to the anus. Its function is to ingest, grind, digest and absorb food, and to eliminate the waste products of the process.

In the monogastric, food is taken into the mouth and mixed with saliva, which starts to break down the starch. The food then goes to the stomach where gastric juices break it down into its component nutrients. Further digestion occurs in the small intestine before nutrients are absorbed into the blood stream and carried to every cell in the body. The watery mass remaining is propelled by means of the muscular movement of the digestive tract into the large intestine which has the important function of absorbing water from it. The large intestine terminates in the anus through which waste products are expelled as feces or manure.

Monogastrics eat both animal and vegetable foods. A monogastric animal usually chews its food before swallowing whereas the ruminant swallows its food after very little chewing. The food is later regurgitated and chewed more thoroughly, hence the word ruminant: an animal that chews its cud.

The diet of a ruminant normally consists mainly of fibrous plant material that requires prolonged chewing, fermentation and soaking before its nutrients are available for digestion and absorption. The compartments in which this takes place are the forestomachs, of which there are three: the rumen, the reticulum and the omasum. The stomach proper, corresponding to the simple monogastric stomach, is called the abomasum.

The rumen functions as a huge 275 litres (60 gal) fermentation vat in which the hay, straw and other foodstuffs are processed for digestion in the true stomach. The microorganisms in the rumen derive their nutrients from the feed consumed by the cow, thereby allowing the cow to utilize high fibre materials such as hay and straw, which cannot be digested by a single-stomached animal. The fibrous plant material is broken down by bacteria and protozoa into a mixture of volatile fatty acids (VFA), which are absorbed into the body through the rumen walls. The bacteria also make the B vitamins and can convert urea or ammonia from non-plant sources into protein.

In addition, the microorganisms pass along the digestive tract with the other food materials and are themselves digested to provide additional energy, high quality protein and other nutrients to the cow.

The reticulum acts in concert with the rumen and serves to trap foreign materials the animal may have swallowed, like wire or nails. The food passes from the rumen through the reticulum to the omasum where the food is ground between projections which radiate from the walls. It then proceeds to the abomasum where digestion proceeds much as it does in the monogastric.

Feeds for beef cattle must supply energy, protein, certain vitamins and minerals. Although different species have different nutritional requirements, there is one principle that applies to the nutritional requirements of all animals; that is, if ample amounts of all nutrients but one are fed, the level of that particular nutrient will limit performance.

The main components of food are water and dry matter. The dry matter consists of organic material and inorganic material.

Water is essential in the transport of metabolic products and wastes throughout the body and for most chemical reactions in the body. The amount of water required varies with the amount of feed consumed, body size, species and the surrounding temperature. However, if water intake declines, feed intake usually declines.

Energy requirement for cattle :

Animals require energy for maintenance, growth, work and for the production of milk and wool. Feeds are evaluated in terms of the amount of energy an animal can obtain from them. The digestible energy (DE) is the gross (total) amount of energy in the hay and grain fed an animal less the amount lost in the feces. Energy is usually reported in megacalories (Mcal) per kilogram. (One kilocalorie is equal to 1,000 calories. One megacalorie is equal to 1,000,000 calories).

Amount of DE needed by an animal per day varies according to body size, weight gain, milk production and work. The amount of energy required to maintain an animal for one day without loss of body weight is called the energy required for maintenance. Most symptoms of slight energy deficiency are not very noticeable: slightly reduced gains, less than maximum milk production and small increases in calving interval. The more severe the energy deficiency, the more noticeable are the symptoms described. Excess energy is stored as fat.

The most common energy source is from the carbohydrates contained in feeds. These are the sugars, starches, cellulose and hemicellulose which have been stored in plant tissues. Chemical reactions which take place in the animal release the energy in the feed (originally trapped from the sun by the plant) and convert it to other forms of energy which the animal can use.

Lipids are another energy source found in plants. They are fats and compounds closely related to them. They contain about two and a half times as much energy as carbohydrates.

Table 1 gives the digestible energy values of some common feeds.

Table 1. Average Energy and Protein Values of Some Alberta Feeds (Dry Basis)

Feedstuff | Digestible Energy (Mcal/kg) | Digestible Energy (Mcal/lb) | Crude Protein (%)* |

| Hay | |||

| Alfalfa | 2.60 | 1.1 8 | 17.7 |

| Alfalfa-grass | 2.46 | 1.12 | 14.5 |

| Native | 2.13 | 0.97 | 9.0 |

| Brome | 2.24 | 1.02 | 9.9 |

| Greenfeed | |||

| Barley | 2.64 | 1.20 | 10.0 |

| Oats | 2.53 | 1.15 | 9.4 |

| Silage | |||

| Barley | 2.64 | 1.20 | 10.9 |

| Oats | 2.53 | 1.15 | 10.0 |

| Straw | |||

| Barley | 1.98 | 0.90 | 4.7 |

| Oats | 2.16 | 0.98 | 4.5 |

| Wheat | 1.80 | 0.82 | 3.9 |

| Grains | |||

| Barley | 3.65 | 1.66 | 12.3 |

| Oats | 3.34 | 1.52 | 11.6 |

| Wheat | 3.87 | 1.76 | 15.8 |

Proteins Nutrients for Cattle:

Proteins are composed of amino acids, which contain carbohydrates, nitrogen and sometimes sulphur. Ten amino acids are essential to monogastrics, whereas ruminants only need a source of nitrogen, or a poor quality protein, from which the microbes in the rumen can then construct the essential amino acids.

Protein is absolutely essential for growth, reproduction and maintenance in monogastrics and ruminants. Mature animals require less protein on the basis of percentage of the feed offered than young ones. Excess protein is utilized as an energy source.

Recommended to feed Amino Power

Minerals Nutrients for Cattle :

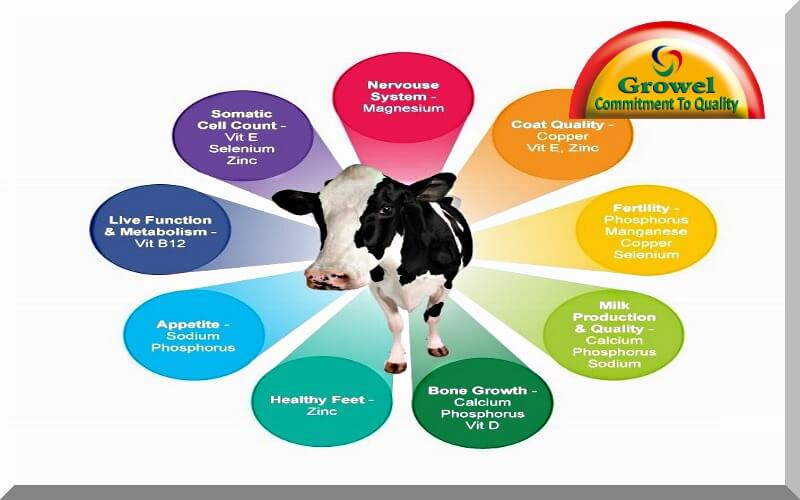

The major minerals in nutrients for cattle are calcium, phosphorus, sodium, chlorine, magnesium and potassium. They are required at comparatively high levels described as percent of diet or grams per day.

An essential mineral performs specific functions in the body and must be supplied in the diet, but too much of any may be harmful or even dangerous.

Calcium (Ca) and phosphorus (P) are the most abundant minerals present in the animal. They are also the ones most often added to ruminant diets. Both are found in the teeth and bones, but calcium is also found in milk and eggs. In addition, Ca is necessary for the clotting of blood, the contraction of muscles, and the functioning of numerous biochemical reactions in the body. All biochemical reactions which allow the energy in food to be utilized by animals require phosphorus.

Animals usually require 1.5 parts of Ca for every part of P. Diets high in legume hay usually require supplemental P only, while diets high in grain often require supplemental Ca. Young animals, including humans, that do not receive adequate amounts of Ca or P may develop rickets, which in cattle show up as arched backs. A deficiency of vitamin D may also contribute to the problem. Older animals fed inadequate amounts of vitamin D develop osteomalacia, the symptoms of which are weak and easily fractured bones. Animals having diets low in Ca and P will show a drop in milk production. A low level of P in the diet may also cause poor reproductive performance in females and lower the availability of vitamin A.

The calcium:phosphorus ratio is very important. It should be more than 1:1 but less than 7:1. If possible, add the proper amounts of Ca and P to cattle diets, or feed it free choice. Mineral supplements formulated for free choice feeding usually have Ca and P present in a 1:1 or 2:1 ratio.

Research has shown that animals on range need supplemental P. Any mineral supplement used should contain at least 14 per cent P.

Sodium and chlorine are found together as sodium chloride (NaCl or common salt) and serve to maintain proper acidity levels in body fluid and pressure in body cells. The hydrochloric acid found in the stomach contains chlorine.

Even though many feeds contain enough sodium and chlorine to meet the requirements of cattle, supplemental cobalt iodized (blue) salt or trace mineral salt should be available at all times.

Potassium (K), like sodium, serves to maintain proper acidity levels in body fluids and pressure in body cells. It is also required in a number of enzyme reactions in carbohydrate metabolism and protein synthesis. Forages normally contain more than adequate amounts of potassium. Supplemental potassium may be necessary for high-grain feedlot diets.

Magnesium (Mg) is necessary for the utilization of energy in the body and for bone growth. Cattle fed on lush, immature pasture may have a low level of Mg in the blood, which can result in grass tetany, a disease characterized by convulsions, twitching of muscles, staggering gait and falling.

Sulphur (S) is a component of body protein, some vitamins, and several hormones. It is involved in protein, fat and carbohydrate metabolism as well as blood clotting and the maintenance of proper body fluid acidity. Most feeds contain adequate amounts of S for cattle. Supplemental S may be necessary when non-protein nitrogen sources are being utilised in high grain feedlot diets.

Recommended to feed Chelated Grwmin Forte

Trace Minerals Nutrients for Cattle :

Feeding trace minerals is not a simple matter. They are required only in very small amounts. Some minerals fed in excess amounts may cause a deficiency in others; a slight deficiency or excess may cause a decrease in performance that is hard to pinpoint. Even though the level in the diet appears adequate, an animal may occasionally respond to an increased supply of a particular mineral because other dietary factors may have decreased its availability.

Iron (Fe) is an essential part of hemoglobin, a compound that carries oxygen in the blood. A deficiency of Fe may cause anemia and reduce growth. Generally there is no need to supply extra iron except to baby pigs. Virtually all feeds in Alberta contain enough iron for cattle, according to analyses done at feed testing laboratories.

Zinc (Zn) affects growth rate, skin conditions, reproduction, skeletal development and the utilization of protein, carbohydrates and fats in the body. While Zn deficiency is not common in ruminants, it can cause a mange-like skin condition called paraketerosis.

Recommended dietary allowance (RDA) is 50 parts per million (ppm), while average concentration in Alberta feeds is 30 ppm. If a supplement is required, it could be supplied in trace mineralized salt, mineral or protein supplement.

A Copper (Cu) deficiency can result in anemia, depigmentation in hair, infertility, scouring, and cardiac failure. Feed testing laboratories find that many samples contain less than the estimated RDA of 10 ppm. Although the symptoms of copper deficiency are rarely evident, improved growth and performance is often seen after Cu supplementation.

Manganese (Mn) is essential for the utilization of carbohydrates. Mn deficiency in cattle in Alberta is rare. Symptoms include retarded bone growth and reproductive failure. The RDA for Mn is 50 ppm; average concentrations in Alberta feeds ranged from 21 ppm in barley grain to 91 ppm in grass hay.

Cobalt (Co) is necessary for the microorganisms in the rumen to synthesize vitamin B12.

Iodine (I) is needed in trace amounts by the thyroid gland, which influences the rate of metabolism in the body. A deficiency causes goitre. As the prairie provinces are deficient in both cobalt and iodine, a salt containing both of these elements must be used.

Molybdenum (Mo) forms an essential part of some enzymes. It may also have a stimulating effect on fibre-digesting microorganisms in the rumen.

Excessive quantities of Mo interfere with the utilization of Cu and may cause a Cu deficiency, symptoms of which include severe scours and loss of body weight. If the diet is high in sulphur, the problem is more severe. Mo-induced Cu deficiency is not common in Alberta.

Selenium (Se) is deficient in some regions of the province and surplus in others. “Alkali disease” or “blind staggers” occurs when cattle eat feed containing toxic or excess amounts of Se (10 ppm) over a long period of time. Chronic toxicity results in loss of weight, dullness, sloughing of hooves and lameness. Toxicity is rare but occasionally found where cattle on overgrazed pasture are forced to eat a milk-vetch that accumulates selenium. The best cure is to remove the animal from the pasture.

Selenium deficiency may result in “white muscle disease” in calves, lambs and foals. A vitamin E deficiency increases the amount of selenium required to prevent this form of nutritional muscular dystrophy. Cows on Se deficient diets may have lower fertility and an increased incidence of retained placentas. The RDA for Se is 200 parts per billion. Se deficiency is quite common in west-central and northern Alberta. Se can be added to salt or mineral mixes, or injected.

Recommended to feed Grow E-Sel

Chromium (Cr), tin (Sn) and nickel (NI) appear to be present in sufficient quantities to meet the requirements of most farm animals.

Fluorine (FI) is essential for proper bone development but will cause toxicity if fed at too high a rate. It is used on domestic water supplies to reduce the incidence of tooth decay. Too much FI causes abnormal bone growth, mottling and degeneration of teeth, and delayed growth and reproduction. To avoid excessive consumption of FI, be sure any rock phosphate fed is defluorinated.

Trace minerals can be effectively supplemented in the diets of cattle by using the proper trace mineralised salt.

Recommended to feed Chelated Grwmin Forte

Vitamins Nutrients for Cattle :

These organic compounds are required in minute amounts by the body. They are essential to metabolism, and some must be supplied in the feed of ruminants.

Vitamin A is the most important nutrients for cattle nutrition. It is the only one that normally must be added to cattle diets. It is necessary for bone development, sight, and maintenance of healthy epithelial tissues (i.e. lining of digestive and reproductive tracts). A deficiency can cause an increased susceptibility to disease, night blindness and reproductive failure.

Vitamin A may be supplied by green forages that contain carotenoids. Carotenoids are broken down in the body to vitamin A. Thus forages are not analysed for vitamin A but carotenoids, which are measured in milligrams per kilogram or pound: mg/kg or mg/Ib.

Cattle can convert 1 mg of carotene to 400 international units (IU) of vitamin A, while chickens can convert 1 mg to 1667 IU of vitamin A.

Animals on green grass can store vitamin A in the liver and draw on it for 2-3 months.

The average carotene value of alfalfa hay is 24.6 mg/lb, but the range of vitamin A equivalent values supplied by alfalfa would be expected to vary from 120 IU to 35,400 IU per pound. Although Alberta forages may contain sufficient carotene to meet all requirements, it is good insurance to feed vitamin A, since the carotene content of a forage declines in storage. Vitamin A is inexpensive. The dry granular product is the most economical source.

Animals may also be injected with a 2-3 month supply. It should be injected twice during the winter.

Water-soluble vitamin A is sometimes added to the water; however, it is difficult to tell whether the animal is getting its daily or monthly quota this way. Mineral supplements should not be relied upon to supply vitamin A as they only contain very small amounts.

Vitamin D is called the sunshine vitamin because ultraviolet light acting on a compound on animal skin changes that compound into vitamin D. Vitamin D is found in sun-cured forages. Animals kept outdoors or fed sun-cured hay do not usually suffer a deficiency, whereas animals kept indoors and fed silage may do so.

Vitamin D is involved in the uptake to Ca and P, so that a vitamin D deficiency resembles a Ca and P deficiency: rickets in the young animals, weak bones in older animals, and a decreased growth rate.

Vitamin E and selenium have similar and interrelated functions in the body. Use supplements containing vitamins D and E in addition to vitamin A. They may not always be necessary but cost little to add.

Recommended to feed Growvit Power

You should also read Importance of Vitamins and Minerals for Cattle.

If you are into dairy or cattle related business & want to earn maximum profit in your business then please join our Facebook group How To Do Profitable Poultry & Cattle farming ?